On Tuesday, sports digital content company Sportico released its NHL team valuations for the 2022/23 season, and despite the rest of the world dealing with the financial crunch, the Board of Governors is likely laughing to the bank. Team valuations have increased by 9% over Sportico’s previous look, and the average team has crossed into the $1 billion franchise value mark for the first time.

Lots of factors go into franchise valuations – sponsorship, revenue, and sales precedent. The latter might be the biggest factor, as sports teams increasingly become the toys of the mega-rich. In North America especially, franchise values began to skyrocket in 2014, when former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer bought the NBA’s Los Angeles Clippers for $2 billion. That benchmark has carried over throughout the association and into the MLB, NFL, NHL, and even MLS in recent years – maybe not at that marquee price as the Clippers are in such a high-value location and the NBA in particular was on the rise, but it set a standard nonetheless.

The full table, posted by Mark Burns on behalf of Axios on Twitter this morning, comes with a couple of interesting nuggets. For example, we have the Canadian teams (ironically, all figures USD):

- Toronto Maple Leafs, $2.1 billion (1st)

- Montreal Canadiens, $1.7 billion (3rd)

- Edmonton Oilers, $1.3 billion (8th)

- Vancouver Canucks, $1 billion (11th)

- Calgary Flames, $870 million (19th)

- Winnipeg Jets, $805 million (22nd)

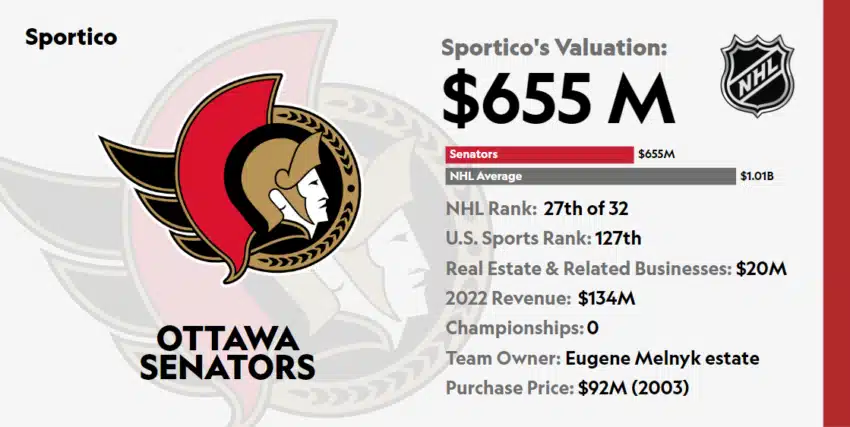

- Ottawa Senators, $655 million (27th)

Toronto and Montreal being near the top is no surprise, but with years of battling with the New York Rangers in mind, it’s still intriguing to see the Maple Leafs take the top seed. While some would assume that the Bell & Rogers-owned, mega-popular club would be a lock for the top seed, the Rangers being in the New York market, and having Madison Square Garden and the associated MSG Network attached to them are huge pulls. Edmonton would historically be considered a team that rides in the bottom half, but the recently-built Rogers Place and the Connor McDavid effect both give the team a kick in the pants financially. Vancouver stays in the top half on raw popularity, while the Flames struggle a little due to the age and uncertainty surrounding their current arena, and future plans.

Lastly, you have the Jets, who play in one of the league’s smallest markets and smallest arenas, but have made the most of their opportunity and sharply increased their value since moving the team to Winnipeg in 2011, and the Ottawa Senators, who just miss the bottom five. The Senators are especially interesting cases, however – no team had a larger year-over-year jump by percentage than the Kanata-based franchise, who have felt the pain from a penny-pinched era under the late Eugene Melnyk, and their own dose of arena uncertainty.

A lot has changed since Melnyk’s passing, under his daughters, who recognize that aggressive growth is the way out of the hole. A strong offseason of on-ice acquisitions, off-ice investments, and a memorandum of understanding that’s initiated the process of building a downtown arena has given an over 20% boost to their value, making this the perfect time for them to cash in and move on. Perhaps not coincidentally, Sportico is reporting that this is the plan. Melnyk’s family has hired Galatioto Sports Partners to explore a sale – the company is also assisting in the sale of MLB’s Los Angeles Angels.

A Little Unfair?

From a personal perspective, it’s hard to look at these increasing valuations and feel like the league is in a healthy spot. Not the old kind of unhealthy spot, where staying afloat was a serious concern – but one where it feels like the practices are detrimental to the product on the ice.

When the NHL instituted a hard salary cap after the 2004/05 lockout, it was decided that this was the best way to keep big teams from lapping minnows, who were bankrupting themselves trying to keep up. The cap would be managed proportionately to league-wide revenues and grow with the proverbial wind.

This arrangement, however, didn’t account for the explosion in team value through indirect means, or the fact that the average owner is worth significantly more on the outside than they used to be. The cashflow of their hockey team means less than ever, and if they ever need to parachute out, the windfall will be significant.

In 2003/04, the last year before the league overhauled it’s financial philosophies, the average team was valued at $168 million. Their payrolls, with no set cap, averaged $44.4 million, with the big spenders being the Rangers at $76.5 million, followed by about half a dozen teams in the $60 million range. Six teams had star players making at least $10 million, with the highest paid (Jaromir Jagr & Peter Forsberg) coming in at $11 million. The average player made about $1.7 million.

This year, the average team is worth $1.01 billion. The league has 29 of its 32 teams sitting within 93% of the salary cap ceiling of $82.5 million, which has moved by just $1 million, or a little over 1% in the last four years. Twenty-one of these teams are projected to close the year within $1 million of this barely-mobile ceiling. Nine teams have star players making at least $10 million, with the highest paid (Connor McDavid) coming in at $12.5 million. The average player makes about $3.3 million.

Essentially, the owners have gotten richer, outside of the league and inside. The salary cap has doubled while team valuations have quintupled. Due to shifts in roster philosophy that identify hockey as a weak-link sport where depth is needed, fringe players have seen gains in their salaries, but the slowly-moving salary cap means that the best players – the ones driving revenue, appearing on billboards, making these teams valuable – make about the same. Roster movement has stagnated and teams are incapable of making the significant changes that create conversation around the league, because a system that was designed to avoid owners who didn’t come in rich getting left behind, has now smushed a bunch of current and future billionaires together with only deliberately losing teams having breathing room in their payrolls, which they rarely use to create a better product.

In fact, let’s spin around to one of those teams to show the absurdity of the new system. The Arizona Coyotes are a team that remain forever controversial, as they don’t pull in the same gate and TV revenues as the rest of the league. The NHL likes to keep them around to extend their market reach, but they’re largely seen as a financial failure. The team is currently in the midst of a scorched-earth rebuild, hoping for a cornerstone players acquired via the draft to save them. They’re deliberately spending as little actual money on players as they can, with a large chunk of their payroll being “dead” cap space devoted to trade retentions, or players on Injured Reserve for the remainder of their deals (which insurance largely pays for in real dollars). The team currently does not have it’s own arena, and is playing in Mullett Arena, owned by Arizona State University with an NHL capacity of just 4600, nearly 80% smaller than the average NHL barn.

The team is by and large hopeless, with no past, present, or future for the average hockey fan to care about. Sportico’s valuation puts them as the least-valuable franchise in the league. They’re currently worth 66% more than the Toronto Maple Leafs were at the start of the salary cap era, and will likely get to the double mark in the next year or two. If even they can be a $465 million dollar operation, does it not stand to reason that tying the players purely to revenue at a rate that grows much slower may have been a mistake?

It’s just a thought.